Character Recognition Using Neural Networks, Polar Coordinates, And Line Orientation

MICHAEL WEINER

Honors Thesis for Sc.B., Cognitive Science

Submitted to Professor James A. Anderson

Brown University • 29 April 1988

Introduction

Character recognition is a task which humans perform with apparently little effort. We recognize letters and numbers of varying sizes, styles, and orientations, and we do this at high speeds almost every time we read. Designing a machine to recognize characters has proven to be a much more difficult task than it might initially appear to be. Although humans can read almost effortlessly, defining explicitly the conditions necessary and sufficient for a pattern to be considered a particular letter is a remarkable challenge. This paper describes my attempts to use neural networks to develop a computer system which recognizes hand-drawn upper-case letters of the English alphabet.

About Pattern Recognition

Surprisingly little is known about human pattern recognition, although there are many theories. The human neural network is formed during embryonic development. The environment in which analysis occurs is often unpredictable, and information is processed through the senses in real time. Since there is no separation of “hardware” and “software”, the system is not “rewired” after each incident of learning; instead, learning is thought to occur when certain synapses are reinforced (Edelman 1982). People use a remarkable amount of previously stored information to recognize new patterns. Consider the pattern in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. A complex pattern which many people can recognize (From Myers 1987, p. 26)

In case you see it as random blotches, it is not; the pattern is a picture of a dalmation (right) sniffing the ground (center). Context and predictions are important in shaping our perceptions. Someone who had never seen a dog before would probably have difficulty recognizing the pattern; someone expecting to see a dog would probably have much less difficulty. “Well-known and expected patterns are more readily recognized than unfamiliar ones. Assumptions and predictions characterize most human perceiving” (Kolers 1968, pp. 15-16). Analyzing patterns requires selective systems which can categorize input. Classification of stimuli is an extremely important human function, since this task forms the basis of perception. Categorization has three basic conditions (Edelman 1982):

- Recognition of similarities among things in the same class

- Recognition of differences among things in different classes

- Recognition of differences among things in the same class

Recognition frequently requires surprisingly broad generalizations, since categories are often very difficult to confine to explicit rules; for example, can you define the properties of a table necessary and sufficient to classify it as such? Exceptions can be found for almost any rule. One early theory of pattern recognition describes the template. Using a template involves matching a pre-defined pattern (the template) directly with the pattern to be tested. The new pattern is compared with many existing templates to see if a match exists. A template has a rigid structure which requires similarity to a test pattern in a most basic, physical form to constitute an instance of recognition. Although it seems that the sensory store can be used for a rapid template match under certain conditions (Reed 1982), pattern recognition almost certainly involves other processes, too. There is overwhelming evidence–the phenomenon of depth perception, reconstruction of information missing from the eye’s blind spot, and a history of research–which suggests that simple image transmission and template-matching are not the only components of pattern recognition. Cortical representation and perceptual experience “are highly recoded abstractions from the retinal image” (Kolers 1968, p. 9).

A popular alternative to the use of templates involves examining some set of features of the input. Examples of physical features include right angles and closed curves. Living systems are known to have feature detectors (Klatzky 1980): people are slower to differentiate two letters if they both contain curves or if they both contain only straight lines (Reed 1982). Cats offer additional evidence for feature detectors: their visual systems have cells which respond to objects having very specific features: some cells respond only to vertical lines, while others respond to horizontal lines, moving lines, or lines of specific lengths.

Yet another aspect of pattern recognition is the structural theory. A structural description of a pattern is a description of how the lines or features of the pattern are joined to each other. Structural descriptions seem to be important in human pattern recognition. Furthermore, there seem to be predominant ways of organizing features of a pattern (Reed 1982), but it is difficult to analyze and formalize these ways, since they are so complex, and involve so many different situations. For example, how do you know that the following figure represents two objects, and not three?

The answer involves a structural theory, that is, a statement about how different portions of the pattern are related to each other.

Human pattern recognition probably involves a combination of each of the three theories mentioned above: templates, features, and structural descriptions. It is quite possible that any one theory dominates at a particular point in the process–for example, templates are created in the visual store–and recognition occurs as a result of the complete chain of processing.

The Experiment

Development

I set out to design a system which would recognize hand-drawn upper-case letters produced in a variety of styles by a variety of writers. I reviewed the many proposed methods and theories of pattern recognition, some of which have been tested.

The template-based method has obvious drawbacks: unless a standard style of print were adopted, each style would require a different template. This would not be practical for recognizing hand-drawn characters, which show continuous variation, even for a single writer. Extracting some set of features from the patterns seems like an appealing alternative with an established cognitive basis. By using this characteristic–the feature detector–in a cognitive system, one can better model actual living systems, and perhaps achieve some interesting and significant results.

Examining features of characters can also solve many common problems with variation in style. A popular technique involves mimicking, in a crude way, living visual systems by detecting the presence of certain patterns, such as  ,

,  , and

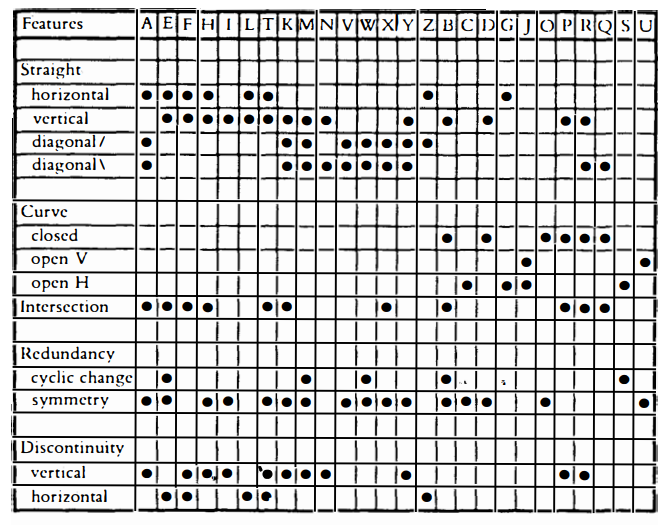

, and  . An example of a set of features (Reed 1982, p. 19) that could be used in a character recognition system is shown in Table 1, below.

. An example of a set of features (Reed 1982, p. 19) that could be used in a character recognition system is shown in Table 1, below.

Table 1. A set of features of upper-case letters (From Reed 1982, p. 19)

One can see from the table that the letter “A” has a horizontal segment, diagonals, intersections, etc. Many algorithms which analyze the input for features, however, still result in errors caused by variation in style, which can be seen in pairs such as  and

and  , or

, or  and

and  . Desirable properties of a feature-based recognition system include the following:

. Desirable properties of a feature-based recognition system include the following:

- To achieve a high degree of accuracy, the number of elements, which represent the full assembly of features, must be large (Edelman 1982).

- The features should yield a unique pattern for each letter (Gibson 1969).

- The number of features should be reasonably small (Gibson 1969).

Structural theory is the basis for another alternative, the incidence matrix (Grenander 1968). An incidence matrix maps intersections, endpoints, and points where the direction of the line changes markedly, to other such points, resulting in information relating parts of the pattern to each other. By this method, then, patterns like  and

and  are recognized as the same letter, since the connections between line segments are the same in each. The extended crossing in

are recognized as the same letter, since the connections between line segments are the same in each. The extended crossing in  , however, causes it to be translated to a different incidence matrix; furthermore, it is interesting to note that

, however, causes it to be translated to a different incidence matrix; furthermore, it is interesting to note that  and

and  have the same endpoints, intersections, and connecting lines, resulting in the same mapping. A mapping like this, which is not one-to-one, is not very useful. Furthermore, because structural information does not exist in fixed amounts, a fixed-size representation is difficult to formulate. As a result, some effective method of making comparisons between representations must be devised.

have the same endpoints, intersections, and connecting lines, resulting in the same mapping. A mapping like this, which is not one-to-one, is not very useful. Furthermore, because structural information does not exist in fixed amounts, a fixed-size representation is difficult to formulate. As a result, some effective method of making comparisons between representations must be devised.

Implementation

Three basic steps in pattern analysis are (1) coding of the input, (2) standardization of the input, and (3) the decision (Grenander 1968). I sought a coding which would be relatively insensitive to both style and size, thus incorporating the standardization step to some extent. I noticed that if I started at some central point in the pattern and drew lines radially outward in all directions, that I achieved the following results: (1) in any given direction, a line drawn outward from the central point intersects the pattern at a particular distance and number of points; and (2) the distance and number of points of intersection change only slightly with variations in style. In fact, Pitts and McCulloch (1947) refer to “invariants of translation” in a human reflex mechanism, whereby the eyes shift to the center of gravity of the distribution of brightness in an image. With this knowledge I began to devise my first test.

I wanted to employ autoassociation and the BSB (“Brain-state-in-a-box”) method (Anderson 1986) of processing vectors, because these techniques model the human nervous system with a simple network of connections. First, the system associates inputs with themselves, using a Widrow-Hoff error-correction scheme. The BSB algorithm, applied later, is an attractor model which approximates pushing a vector of many dimensions into one corner of a hypercube. Added advantages include a large number of elements, resistance to noise, and the ability to map any set of features to some particular, closest-matching set.

A binary coding would probably work best with the processor. I first thought of a “purely visual” coding. Each radial line would determine five bits. The radial line was divided into five equal segments, ending at the overall radius of the pattern. The leftmost of the five bits would represent the portion of the radial line close to the center of the pattern; the rightmost bits were for the peripheral parts. If some fifth of the given radial line intersected the pattern, the appropriate bit would be marked with a one; otherwise, the bit would be zero.1

I wanted similar patterns to have similar codings. To the BSB processor, however, which uses linear algebra, a coding like 01000 is as different from 10000 as it is from 00001. This would deter from the accuracy of recognition using a direct coding like the one described above. To solve the problem, I would have to use five bits not for all intersections of one radial line with the pattern, but for just one such intersection. I marked with ones all bits to the left of and including the bit corresponding to an intersection. With this scheme, what might have been 00100 became 11100. The coding 11100 resembles 11000 more than it resembles 10000. These results match those obtained by altering the corresponding patterns slightly.

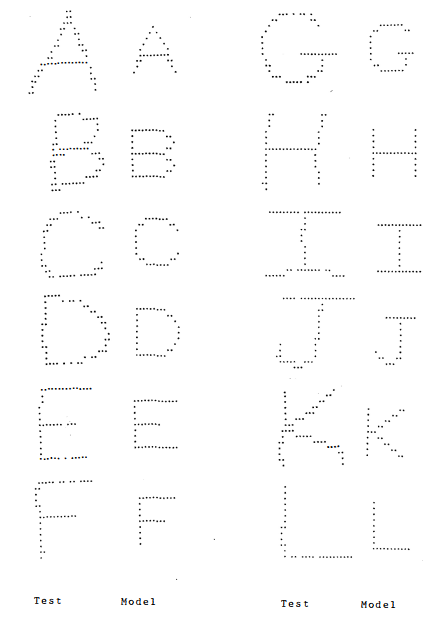

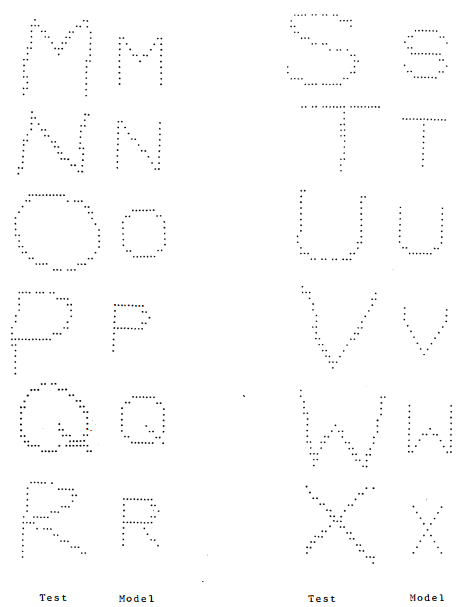

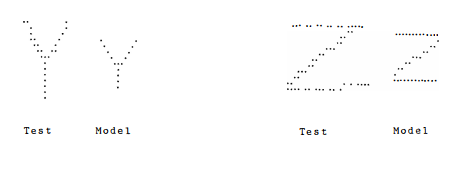

I encoded only the innermost and outermost intersections, yielding ten bits per radial line. A dimensionality of 200 allowed for 20 radial lines, or what grew to be “pie slices” to account for noise (points missing from the pattern). I used a mouse-controlled BITPAD to create a model set of what I considered “perfect” letters, and a set of test patterns drawn quickly and naturally by me. They are shown in Appendix A, below. Autoassociation was used to train the system with the model set, resulting in a 200 x 200 matrix. The program was written in PASCAL and executed on a VAX. It is listed in Appendix C.

I needed a way to determine an appropriate central point. I could average the extreme coordinates, but then wild, extending lines in the pattern would throw off the centerpoint substantially. I decided to use the center of mass of the points, since it is resistant to single small changes in the pattern.

Decisions were made as follows: first, the BSB nonlinearity was applied to each model vector, and the 26 resulting “BSBed” vectors were stored. To find a match for a test vector, BSB was applied to the vector, and then the most similar2 of the BSBed model vectors was considered a match.

Experiment 1

Thirty presentations of each model character were used to train the system. Of 26 characters, only nine were not recognized. They are shown in Table 2, below.

Table 2. Errors using a polar system which detects innermost and outermost points of intersection with radial lines

| Actual character | Match found | Human error |

|---|---|---|

| C | O | yes |

| G | Q | yes |

| H | W | yes |

| P | F | yes |

| Q | S | no |

| R | E | no |

| X | N | no |

| Y | T | yes |

| Z | B | yes |

| Total errors: 9 |

The column labeled “Human error” indicates whether similar mismatches occurred in a test of human subjects.3 The complete chart of human errors is shown in Appendix B. Six out of the nine errors also occur in human subjects. Intuitively, it is easy to see how these errors can occur; ‘F’ and ‘P’ overlap almost completely, as do ‘C’ and ‘O’. A ‘T’ with a curved top resembles a ‘Y’.

Experiment 2

One problem with using the center of mass as a central point is that this causes letters like ‘T’ and ‘Y’ to have very similar codings. Because only the innermost and outermost points of intersection were encoded for each radial slice, letters like  and

and  also had overlapping codings. If a mid-range point of intersection were used, rather than an innermost point, perhaps some of the ambiguities could be eliminated.

also had overlapping codings. If a mid-range point of intersection were used, rather than an innermost point, perhaps some of the ambiguities could be eliminated.

The results of this change followed expectations. Using points of intersection at mid-range and outermost distances, only six of the 26 characters were not recognized correctly. They are shown in Table 3, below. Four out of the six errors also occur in human subjects.

Table 3. Errors using a polar system which detects mid-range and outermost points of intersection with radial lines

| Actual character | Match found | Human error |

|---|---|---|

| C | O | yes |

| G | B | no |

| H | M | yes |

| P | R | yes |

| S | B | yes |

| Z | R | no |

| Total errors: 6 |

One weakness of the radial technique is that it hinders recognition of letters affected by stretching distortions in one direction. For example, if  is learned,

is learned,  would not be recognized correctly. Although I did not employ a normalization scheme to correct this weakness, such a procedure would be necessary if the radial system were to recognize letters of a wide variety of styles. This process is part of the standardization step.

would not be recognized correctly. Although I did not employ a normalization scheme to correct this weakness, such a procedure would be necessary if the radial system were to recognize letters of a wide variety of styles. This process is part of the standardization step.

Although in designing this radial, or polar, method of recognition, I examined features of letters, I do not consider it an ad hoc method, because it neither requires the presence of certain letterlike features, nor requires that letters be the patterns being recognized. The method could be used to recognize all kinds of pictures. It is simply sensitive to certain features, rather than others. After I experimented with the system, I was eager to test some of the popular techniques based on orientation of line segments. I reviewed an interesting line-tracing algorithm (Mason and Clemens 1968)–that is, a way to trace the pattern from point to point in an orderly fashion, using directions of the tracing movement as a way to detect line segments of a particular orientation. Unfortunately, the simple tracer I examined does not handle noise with much skill. Missing points–especially on diagonals–often confuse it, leaving portions of the pattern unnoticed. There were other subtle complications, such as ensuring detection of all areas in the pattern, marking areas already examined, and accounting for large gaps. Although in later experiments I employed a “filling” routine to correct some effects of noise, I did not implement a tracer successfully. The tracer’s problems are rooted in its failure to involve structural theory. Tracing a complex path in a sophisticated fashion probably requires integrating structural information during the trace.4 The importance of incorporating structural description into a cognitive model of recognition can be seen easily by reviewing Figure 1.

Experiment 3

Certainly, if I examine any column in my grid of points and spaces, if there is some minimum number of points in the column, then a vertical line segment is present. Because of the noise caused by the input device, I decided to examine vertical “bars”–sets of adjacent columns–rather than single columns. A hybrid system was created to test the scheme. I reduced the number of bits of the previous polar system from 200 to 180, and substituted 20 bits of encoded information about line orientation. Six segment types were detected: left- and right-slanting diagonals, vertical segments to the left and right of center, and horizontal segments above and below center. All vertical and horizontal segments were represented by three bits: 000 for no segments present, 100 for one segment, 110 for two segments, and 111 for three or more.5

I used a bar width of 2 to 3, and assumed a critical number equal to some fraction–typically, 0.6–of the pattern radius; if the pattern radius were ten, for example, then six points in a vertical bar of width 2 must be present to assume that the bar contains a vertical segment. This modification showed no improvements over the first test. Results are shown in Table 4, below.

Table 4. Errors using a hybrid system: polar coordinates and line orientation

| Actual character | Match found | Human error |

|---|---|---|

| A | P | no |

| C | O | yes |

| G | B | no |

| H | W | yes |

| R | P | yes |

| S | B | yes |

| X | K | yes |

| Y | T | yes |

| Z | R | no |

| Total errors: 9 |

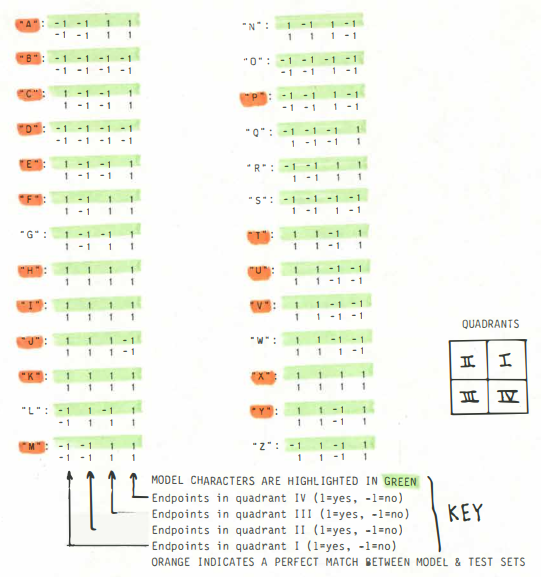

Although a large assembly of information concerning orientation of line segments can result in unique codings for each letter, only the limited information described above was tested with this system. Perhaps the greatest problem with using a line-oriented approach, however, is that hand-drawn letters do not support it; that is, they often differ from printed letters, resulting in many differences in line-based information. An inspection of Appendix A will clarify this intuitively. Actual differences in codings between model and test sets of data used in this system can be seen more clearly in Table 5, below.

Table 5. Model and test characters: information about line segments

Experiment 4

In a fourth test, the position of endpoints was introduced into the coding. An inspection of Table 6 shows that this information is more consistent across the two sets of data than information about line segments. Comparing model with test data, Table 5 shows 6 perfect matches of line-based information, while Table 6 shows 17 perfect matches of information about endpoints.

Table 6. Model and test characters: information about endpoints

Results of the test are shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7. Errors using a hybrid system: polar coordinates, line orientation, and position of endpoints

| Actual character | Match found | Human error |

|---|---|---|

| B | S | yes |

| H | M | yes |

| R | P | yes |

| X | K | yes |

| Y | T | yes |

| Z | E | no |

| Total errors: 6 |

This test was most successful, since 5 of 6 errors correspond to similar human errors.

Other tests

Several other tests were performed. One was designed to determine the effect of learning the test set of data following training with the model set. Another test examined the effect of shifting the non-linearity to a later stage. Yet another test examined the effect of generating the vectors of comparison at a different stage during the learning process. Other tests were also performed, such as training only with test data.

Many of the tests improved some areas of performance, but no test of a broad but reasonable sample of test input resulted in fewer than five errors out of 26 letters tested.

Summary of results; comparative performance

The most successful model tested here yielded a recognition rate of about 77%. The table in Appendix B shows that if a random alphabetic error were to occur, it would correspond to a similar human error only 9% of time (60/676). The random chance that 5 out of 6 errors match human errors, as they do in Experiment 4, is extremely small (p < 0.001). Therefore, the model is significant in its cognitive mimicry.

Many studies have been performed using a wide variety of techniques. In a study by Dydyk and Kalra (1970), for example, a character was matched simply to 1 of 4 subsets of shapes. A vector representing 18 features was then compared with previously stored data to make a match. The recognition rate of that model was 65%, lower than that of the present model.

Although the present model performs better than the simplest models tested, many other models which involve training and testing with thousands of sets of data perform quite well. Some tests, including ones which involve sophisticated smoothing and filtering algorithms, have yielded recognition rates as successful as 99.64% on some sets of data (Suen et al. 1980). Unfortunately, limits of time and resources prevented testing the present model with large numbers of samples.

Discussion

The strictly “polar” model is especially interesting, since its physiological correlate is hardly understood. Pitts and McCulloch (1947) write (p. 146):

The adaptability of our methods to unusual forms of input is matched by the equally unusual form of their invariant output, which will rarely resemble the thing it means any closer than a man’s name does his face.

The polar model tested herein showed fairly impressive results, both in its correct matches, and in the closeness of its errors with errors of human subjects. The system described is not intended to model a human brain; the structure of the system, however, gives it the apparently intelligent ability to generalize upon and learn new information. This ability is emphasized by the fact that training occurred only with model data, but recognition occurred with test data.

Mental rotation is a significant psychological phenomenon not accounted for in this model. Humans can recognize rotated characters, like  , in a time proportional to the angular distance traversed in rotating the character to an upright position (Klatzky 1980). If a way to rotate input were employed, however, it would probably involve rotating the character to maximize the number of vertical and horizontal segments. By its nature, mental rotation must involve ad hoc methods. It would seem to involve a complex template-based matching scheme with fast parallel operation. For my system to perform rotation, it might perform a series of rotations, testing for segments each time, and eventually finding the closest match to an upright figure. This process is time-consuming and cumbersome for the common serial computer. A proper cognitive model, however, must account for rotation, and must perform rotation quickly.

, in a time proportional to the angular distance traversed in rotating the character to an upright position (Klatzky 1980). If a way to rotate input were employed, however, it would probably involve rotating the character to maximize the number of vertical and horizontal segments. By its nature, mental rotation must involve ad hoc methods. It would seem to involve a complex template-based matching scheme with fast parallel operation. For my system to perform rotation, it might perform a series of rotations, testing for segments each time, and eventually finding the closest match to an upright figure. This process is time-consuming and cumbersome for the common serial computer. A proper cognitive model, however, must account for rotation, and must perform rotation quickly.

We know that there are living visual systems which have detectors able to sense features such as line orientation. The improvements in this experiment which resulted from including such feature-based information support the usefulness of the feature detector. A polar system like the one described herein, however, and one described by Pitts and McCulloch, may also have important consequences at some relatively high level in the human processing system. The relative success of the polar system suggests not only the possibility of polar encoding of information, but also emphasizes the general importance of higher-level processing in the human visual system. Even with feature detectors, the mere knowledge of existence and most general placement of horizontal and vertical lines, for example, does not seem to be enough to determine a single character. It seems that more complex information, such as relative positioning of specific lines and awareness of subtle differences between shapes, is essential for consistent, accurate character recognition.

Conclusion

A system for recognizing hand-drawn upper-case letters has been described. It uses a neural network with autoassociation to learn a model set of characters. The BSB nonlinearity is employed to classify the input in order to find a closest match. The first model uses polar coordinates to encode radial information about the input. The second model is a hybrid of the first model with information about vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines detected in the input. A third model encodes additional information, about end-points. The models tested normalize the input for size and translation in the field. The best model incorporated the most information about the pattern, including polar information, information about segment orientations, and the position of endpoints. The rate of recognition was 77%, a value comparable with those from previous studies, but much lower than human rates of recognition around 96%. The similarity of errors to those of human subjects confirms the model’s cognitive significance.

Human pattern recognition seems to be an extremely complex process closely tied with perception. It involves the ability to generalize on a very broad scale, apparently incorporating information at many levels, such as levels of immediate physical input, feature- and structure-based analyses, and prior experience. Despite the success of some man-made systems using limited sets of data, few systems which recognize hand-printed characters are actually in use, presumably because of inconsistencies across larger samples. The great discrepancy between our ability to recognize a relatively simple system of letters and our ability to formalize our own internal systems accentuates the natural powers of the human mind.

Appendix A: Model and test letters used for recognition

Appendix B: Character-recognition errors in human subjects

Appendix C: Listing of the program

http://thesis.cogit.net/neuralnetworks-brownunivthesis-weinermichael-880429-program.pdf

Bibliography

Agrawala, Ashok K., ed. 1977. Machine Recognition of Patterns. IEEE Press, New York.

Anderson, James A. 1987. Lectures in neural modelling. Brown University, Providence, RI.

Anderson, James A. 1986. Practical Neural Modelling. In press.

Anderson, James A., and Mozer, Michael C. 1981. Categorization and selective neurons. In Parallel Models of Associative Memory, pp. 213-36. Edited by Geoffrey E. Hinton and James A. Anderson. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, Hillsdale, NJ, 1981.

Baron, J. 1978. The word-superiority effect: Perceptual learning from reading. In Handbook of Learning and Cognitive Processes. Edited by W. K. Estes. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. Cited in Reed 1982.

Chandrasekaran, B.; Kanal, L.; and Nagy, G. 1969. Report on the 1968 IEEE Workshop on Pattern Recognition. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., New York.

Changeux, Jean-Pierre; Courrege, Philippe; and Danchin, Antoine. 1973. A theory of the epigenesis of neuronal networks by selective stabilization of synapses. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 70:2974-78.

Changeux, Jean-Pierre; and Danchin, Antoine. 1976. Selective stabilisation of developing synapses as a mechanism for the specification of neuronal networks. Nature 264:705-12.

Charniak, Eugene, and McDermott, Drew. 1985. Introduction to Artificial Intelligence. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Reading, MA.

Chaudhari, Nirupa, and Hahn, William E. 1983. Genetic expression in the developing brain. Science 220:924-28.

Dydyk, R. 8., and Kalra, S. N. 1970. Macro feature extraction for character recognition. IEEE Conf. Rec. Feature Extraction and Selection in Pattern Recognition (October, pp. 39-48). Cited in Suen et al. 1980.

Edelman, Gerald M. 1982. Through a computer darkly: group selection and higher brain function. Bulletin of The American Academy of Arts and Sciences XXXVI:20-49.

Edelman, Gerald M., and Finkel, Leif H. Neuronal group selection in the cerebral cortex. In Dynamic Aspects of Neocortical Function. Edited by G. M. Edelman, W. M. Cowan, and W. E. Gall. John Wiley and Sons, New York. In press.

Eden, Murray. Handwriting generation and recognition. In Kolers and Eden 1968.

Engel, G. R.; Dougherty, W. G.; and Jones, G. Brian. 1973. Correlation and letter recognition. Canad. J. Psychol./Rev. Canad. Psychol. 27:317-326.

Fujii, Katsuhiko, and Morita, Tatsuya. 1971. Recognition system for handwritten letters simulating visual nervous system. In Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, pp. 56-69. Edited by K. S. Fu. Plenum Press, New York, 1971.

Gibson, Eleanor. 1969. Principles of Perceptual Learning and Development. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York. Cited in Reed 1982.

Grenander, U. 1968. Linguistic Tendencies in Pattern Analysis. Brown University, Providence, RI.

Grenander, U. 1978. Pattern Analysis: Lectures in Pattern Theory, vol. II. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Kinney, G. C.; Marsetta, M.; and Showman, D. J. 1966. Studies in display symbol legibility, part XII. The legibility of alphanumeric symbols for digitalized television. The Mitre Corp., Bedford, MA. Cited in Lindsay and Norman 1972.

Klatzky, Roberta L. 1980. Human Memory: Structures and Processes. Second ed. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York.

Kolers, Paul A. 1968. Some psychological aspects of pattern recognition. In Kolers and Eden 1968.

Kolers, Paul A., and Eden, Murray, eds. 1968. Recognizing Patterns: Studies in Living and Automatic Systems. The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, MA.

Lindsay, Peter H., and Norman, Donald A. 1972. Human Information Processing: An Introduction to Psychology. Academic Press, New York.

Mason, Samuel J., and Clemens, Jon K. 1968. Character recognition in an experimental reading machine for the blind. In Kolers and Eden 1968.

McCall, Robert B. 1980. Fundamental Statistics for Psychology. Third ed. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., New York.

McClelland, James L.; Rumelhart, David E.; and the PDP Research Group. 1986. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, vol. 2: Psychological and Biological Models. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Mclachlan, Dan, Jr. 1961. Similarity function for pattern recognition. Journal of Applied Physics 32:1795-96.

Myers, David G. 1987. Social Psychology. Second ed. McGraw-Hi11 BooK Company, New York.

Nagy, George. 1982. Optical Character Recognition–Theory and Practice. In Handbook of Statistics. Edited by P. R. Krishnaiah. Vol. 2: Classification Pattern Recognition and Reduction of Dimensionality, edited by P. R. Krishnaiah and L. N. Kanal. North-Holland Publishing Company, New York, 1982.

Nestor, Inc. 1986. NLS Technology Overview: Nestor Learning System.

Pitts, Walter, and McCulloch, Warren S. 1947. How we know universals: the perception of auditory and visual forms. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 9:127-47.

Reed, Stephen K. 1982. Cognition: Theory and Applications. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, Monterey, CA.

Reeke, Jr., George N.; and Edelman, Gerald M. Selective networks and recognition automata. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. In press.

Reilly, Douglas L.; Cooper, Leon N.; and Elbaum, Charles. 1982. A neural model for category learning. Biological Cybernetics 45:35-41.

Rumelhart, D. E. 1970. A multicomponent theory of perception of briefly exposed stimulus displays. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 7:191-218. Cited in Reed 1982.

Schantz, Herbert F. 1982. The History of OCR: Optical Character Recognition. Recognition Technologies Users Association.

Schwab, Eileen C., and Nusbaum, Howard C., eds. 1986. Pattern Recognition by Humans and Machines. Vol. 2: Visual Perception. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, Boston.

Sperling, G. 1960. The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs 74. Cited in Reed 1982.

Suen, Ching. Y.; Berthed, Marc; and Mori, Shunji. 1980. Automatic recognition of handprinted characters–the state of the art. Proceedings of the IEEE 68:469-87.

Get the original thesis document in PDF

http://thesis.cogit.net/neuralnetworks-brownunivthesis-weinermichael-880429.pdf

http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9777269-

In actual practice, all bits 0 were changed to -1. Thus the final vectors contained decimal values of either 1 or -1. ↩

-

The similarity of two vectors was measured by the cosine between them. ↩

-

The “direction” of the human error is not considered in this analysis. For simplicity, letters shown and letters called were considered reversible. See Appendix B. ↩

-

Of course, parallel architecture would be convenient for such parallel processes. ↩

-

Again, -1 replaced 0 in the final implementation. ↩